The Wolfson Building by Louis Kahn

|

The Wolfson Building for Mechanical Engineering, the main building of the Faculty of Engineering at Tel Aviv University, is often perceived as gloomy by its occupants. However, its history and underlying ideas may inspire both users and visitors to reflect more deeply. Planning began in the late 1960s, and the building was completed in 1980, six years after the death of its architect, Louis Kahn, one of the foremost architects of the 20th century. Among Kahn’s most famous projects are the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in California, the National Assembly Building of Bangladesh, and the Kimbell Art Museum in Texas (which resembles some of the halls in the Wolfson Building). Photographs taken during construction illustrate Kahn’s sculptural style and architectural power.  The Wolfson Building during construction. Pictures from Josep Maria Torra Flickr’s account. Images included in this post are used for academic criticism, commentary, and analysis, in accordance with the principles of fair use. The article by Jeremie Hoffmann and Hadas Nevo-Goldberst, Louis Kahn in Tel-Aviv (PDF is available here), describes the architectural ideas behind the project: at the time, new campus buildings at Tel Aviv University were designed in a brutalist architectural style, emphasizing exposed construction materials — especially raw concrete — without concealing them. The Wolfson Building is located along the campus’s central inner promenade, and its prominent front façade faces that path. It consists of a massive windowless concrete wall, punctuated only by narrow vertical slits that subtly indicate the entrance. The contrast between the monumentality of the mass and the small entryway heightens the sense of awe and marks a dramatic transition from exterior to interior.  The Wolfson Building during construction. Pictures from Josep Maria Torra Flickr’s account. Images included in this post are used for academic criticism, commentary, and analysis, in accordance with the principles of fair use. The building is divided into two main sections. The western part — the primary mass — includes classrooms and faculty offices surrounding a five-level inner courtyard. This courtyard was designed as an open-air amphitheater under the sky, serving as a gathering space for the academic community. The combination of offices, classrooms, and laboratories creates a “mixed use” within the faculty. It is easy to catch a lecturer for a quick chat on the way to class, and during the semester, the corridors hum with academic activity.

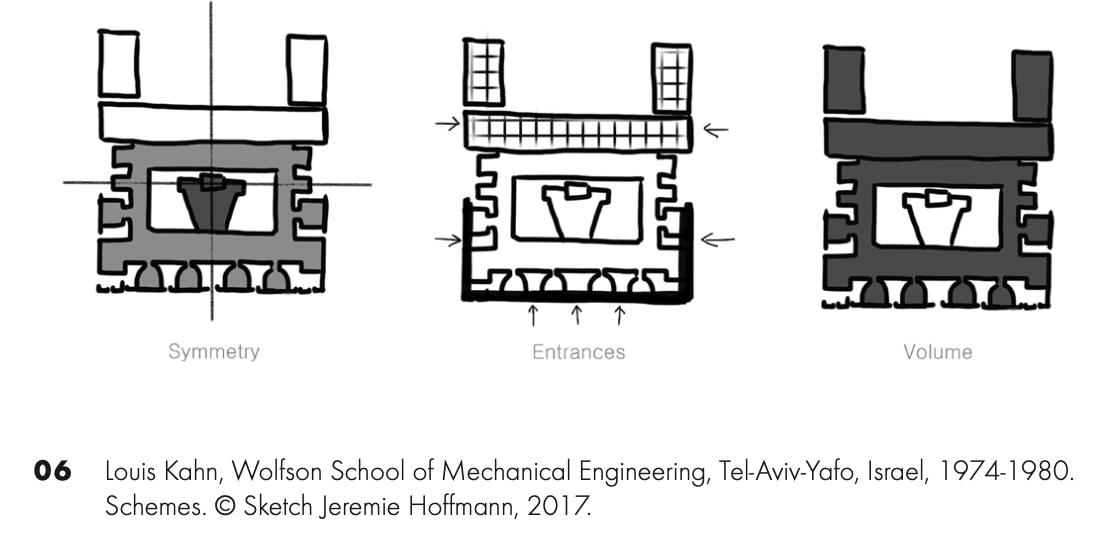

Plumbing, ventilation, and fresh air systems are concentrated in circular ducts (“nostrils”) distributed along the structure, giving the building a distinct appearance both inside and out. Over the years, changes to the building have dimmed Kahn’s original vision. The original wooden doors, which softened the impression of the brutalist concrete, were replaced with standard doors. Entrances that allowed for natural student and visitor flow throughout the building were closed, causing overcrowding at the main entrance.  Sketch by Jeremie Hoffmann, 2017. Since its completion, the Wolfson Building has become a landmark of architecture in Tel Aviv and has significantly influenced other projects in Israel. For example, architect Asaf Lerman explained in a Haaretz article that the inspiration for the Technological Incubator building in Katzrin came “from the iconic engineering building at Tel Aviv University.”  Startup Incubator in Katzrin / Asaf Lerman. Photographs: Amit Geron Although Kahn had proposed several ideas for buildings in Israel — such as a plan to rebuild the Hurva Synagogue in Eastern Jerusalem’s Old City, the Engineering Faculty was the only one that came to fruition. Yasir Sakr’s book The Subversive Utopia: Louis Kahn and the Question of the National Jewish Style in Jerusalem describes Kahn’s unbuilt design for the Hurva Synagogue in Jerusalem’s Old City, and its cultural and political implications. Commissioned after the 1967 war. If you want to learn more, you’re welcome to:

I recently stumbled upon pictures taken in 1978 documenting the construction of the building. The sheer power and simplicity of the building are visibly apparent in those pictures (see an example below), especially before the more recent additions. Note that the images included in this post are used for academic criticism, commentary, and analysis, in accordance with the principles of fair use.

|